And you are?

I am a writer. I earned my master’s in fine arts for creative writing in 2003. It would seem that those two ideas should be in one sentence. I’m one of those women from a young age who loved writing poetry, short stories and watched in awe as friends became enmeshed in a world of words. After all, mine was just a “hobby.” They were Writers. I passed up opportunities to write for publication because I didn’t feel I was good enough. Then I enrolled for my master’s in creative writing, because it was something I thought I had to do to call myself a Writer. I graduated with a draft of a novel and the belief that I would take publishing by storm. While fellow graduates managed to get their books published, I wallowed in the self-pity of remaining “unpublished,” never able to quite find an agent who would take on this dewy-eyed Writer. I landed at the local newspaper and started having a byline in the paper and in its magazine. I freelanced on the side. I was sheepish about it. I met up with a friend, whose book had just been published. At one point, as she gushed about her success and briefly asked about my job, she asked if I still considered myself a Writer. I thought back to all that I had written since graduation. I multiplied that to the readership of the publications I wrote for and responded that I did. However, her comment stung. I realized that I consider myself—and always have considered myself—a writer. I may never become a Writer. But I am okay with that. For a year, I’ve been a full-time freelance writer. I write blogs, and for the newspaper, the local women’s magazine and an area business journal. In my spare time, I read my children’s fiction to my oldest children. Their passion for my fiction is endearing—and rewarding in itself. And, while my unpublished novel and children’s stories may collect dust long after I am long gone, each week, it never fails. I meet someone at my children’s school or at the dentist’s office who will say, “I just saw that article you wrote. I didn’t know you are a writer.” I look them in the eye and say, “Yes, I am—and so much more!” Elizabeth King Humphrey is a creativity coach and the moderator/main blogger for CoastalCarolinaMoms. She is also a freelance writer, columnist and blogs for wilmaville. To have the opportunity to listen to read her children's stories, stop by prior to bedtime most any night of the week. Labels: writer mom, writers perspectives, writing advice, writing life

Do They Get It?

If you live with people who aren't writers, but "get" your writer's lifestyle, consider yourself lucky. If, on the other hand, you're like many writers whose family and significant others don't really get it, you're in the majority. Do you hand your husband or wife your latest short story to review, a story which took you two months to write, edit and polish to perfection? Do they read it and then say, "That's nice, dear" before going back to the TV/newspaper/garden? Does that make you want to scream, "But reread that fourth paragraph! Look at how skillfully I've used flashback there! And what about how I described the old man? Just look at that!"? Instead of screaming, many of us quietly take our stories, our carefully crafted babies if you will, and look at them with a pride only a parent can feel. They don't get POV, foreshadowing, a turn of phrase that gives us goosebumps. They don't understand why we huddle over a keyboard that doesn't dole out rewards or praise, or why we'll jump out of bed at 3 o' clock in the morning to jot down sudden inspiration. They can't quite see all of the nuances that separate a mediocre story from a masterpiece. They just don't get it. But if they're still willing to put up with some of the more well-known writers' idiosyncrasies, if they love you anyway, they can't be all bad. After all, I don't get why my husband has to visit Home Depot every.single.Saturday.morning either. Labels: Del Sandeen, Family, writers perspectives, writing, writing craft

It May Take Too Much Time

I worry about the amount of time that good writing takes, sometimes letting it stop me from writing anything at all. Will trying to put together this potential essay be a waste of time, I'll wonder? Won't crafting that marketable article or story take up too much time, I'll think. I'm not the fastest writer. Rather, I should say, at this point it often takes a lot of rewrites to get it right. Looking through an old folder recently, I came across a heavily marked draft of some work, a piece of writing now finished, which I am proud of in its final form. I forgot how much work had gone into that project until I saw evidence of all the editing. Some writing just takes a lot of pondering and polishing, and viewing those particular pages reminded me that the effort in that case was well worth it. Writers will freely admit they don't bang out first drafts that are ready to go out into the world as soon as the ink dries. Therefore, there is no need to expect perfect first pages. A certain amount of changes will be needed. If you need a lot of time to get a piece right, I now tell myself, then so be it. When it's done, you will have something in hand you're pleased with, even if it took some effort, perhaps more effort than it might take someone else. Good writing takes time. It’s okay to create many drafts before there is something worthy to show. No one sees the process! No one knows about the earlier drafts! What matters is that you end up with a finished product that's good--no matter how long it took you to get there. Plus, as Ernest Hemingway said, "It's none of their business that you have to learn how to write. Let them think you were born that way." -MP Labels: attitude, Being a Writer, editing, Marcia Peterson, time, writers perspectives

Women as Writers: Take What's Useful...

A few months ago, I seemed to keep running into the same theme concerning women as writers: that once women start families, the vast majority of them stop writing. I read it in Alice Walker: A Life, where she recalls one encounter with a woman she upset with her assertion that having more than one child hampers a woman's full creativity (I'm paraphrasing). Ms. Walker, of course, only had one child. The woman who reacted was bothered by the assumption, prompting her to write a letter to the author, who in turn told the woman that she should take what is useful and ignore the rest. On one hand, I often say that same thing: take what is useful and ignore the rest. On the other hand, it does nag at me when I continue to run into the idea that women aren't allowed their full creativity when children come on the scene. When men become fathers, no one expects them to stop writing, but for women, who most often are the primary caregivers (whether they work outside of the home or not), unless she's a bestselling author, she can be expected to put her writing on the back burner. If you've always been a writer, this can be akin to setting your dreams on the back burner, on a low fire and watching it slowly die. Yes, it can be more difficult to find time to write when you have children, but if writing is truly your passion, what you were called to do, then it shouldn't matter if you have one child or five or ten. We all find time for what we truly value, whether it's reading, exercising or scrapbooking. Of course, this may hit closer to home if you're a mother, but whether you have children or not, take what's useful: you're a writer, and ignore the rest: the idea that women always have to sacrifice the best of themselves. Labels: Creativity, Family, life and writing, Mom writers, mother, women writers, writers perspectives, writing, Writing Moms

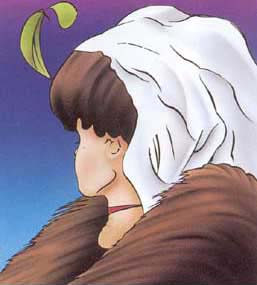

Flexing a Writer’s Perspectives

Every classroom of writing students requires flexible group dynamics. Teaching, in general, requires an open-minded ability to facilitate learning for all personality-types and individuals of diverse backgrounds, including gender, job experience, lifestyle, age (meaning life-experience skills, in this sense). College instructors, secondary school teachers, and all teachers certainly need energy to teach any subject to all students. The best memories from my college English composition course lessons linger from my students’ diverse perspectives and the infinite number of ways each one could perceive the same subject. When I taught three courses with thirty-five students per class, and I used the same writing exercises for each one, I came away with 105 different writing perspectives. Two of my favorite exercises involved teaching description, how to look for it, and how to write it down on paper so readers could sense objects and subjects through the writer’s eyes, ears, nose, taste buds, and finger tips, or whichever senses applied. Of course, this involved teaching how to be aware of one’s sensory perceptions and how to capture them on paper. For example, I’d used one of Annie Dillard’s passages from “Death of a Moth” to illustrate the use of details. Here it is: “One night a moth flew into the candle, was caught, burnt dry and held. I must have been staring at the candle, or maybe I looked up when a shadow crossed my page; at any rate, I saw it all. A golden female moth, a biggish one with a two-inch wingspread, flapped into the fire, dropped abdomen into the wet wax, stuck, flamed, and frazzled, in a second. Her moving wings ignited like tissue paper, like angels’ wings, enlarging the circle of light in the clearing and creating out of the darkness the sudden blue sleeves of my sweater, the green leaves of jewelweed by my side, the ragged red trunk of a pine; at once the light contracted again and the moth’s wings vanished in a fine, foul smoke. At the same time, her six legs clawed, curled, blackened, and ceased, disappearing utterly. And her head jerked in spasms, making a spattering noise; her antennae crisped and burnt away and her heaving mouthparts cracked like pistol fire. When it was all over, her head was, so far as I could determine, gone, gone the long way of her wings and legs. Her head was a hole lost to time. All that was left was the flowing horn shell of her abdomen and thorax--fraying, partially collapsed gold tube jammed upright in the candle’s round pool.” In the previous passage, I’d asked my students to consider the following questions: 1. How many abstractions do you find in the passage? 2. How many specific and concrete terms are there? 3. How does Dillard achieve startling precision and grace? I’d provided more questions for my students, but this is just a sample. By examining Dillard’s perspective, students had a clear example from which they could practice their own writing. Another exercise to push students beyond the day-to-day “thought box” included particular 3-D images or optical illusions. A great place to go for practice is the Third Side Perspective. As students decided on their perspectives, on various pictures like those provided at the Third Side, I asked them to write a descriptive passage as detailed as possible. These exercises enabled students to approach writing from a reader’s perspective and learn how to apply their senses like Dillard. They had to think about how to “show” their subjects for readers. For instance, when you glance at the picture atop this Blog, what do you see? Of course, you might see one of two images, or both: an old lady and/or a young woman. How would you describe the picture provided here? These exercises can work for anyone. Our perspectives can be captured on paper or on a blank screen for others to see, hear, touch, taste, or feel. We need only think outside ourselves. How do you flex your perspective or practice drawing pictures and scenes with words? Labels: craft of writing, sensory writing, Sue Donckels, writers perspectives

|