riters who have grown through work with a strong critique group can tell you: That a cluster of women is a treasure to be respected and handled with exquisite care. Critique groups help fledgling writers build confidence and help maturing writers find their way to publication and beyond. Such groups offer a forum for questioning, learning, practicing, encouraging, mentoring, commiserating, and warming one's self-image with the glow of accomplishment.

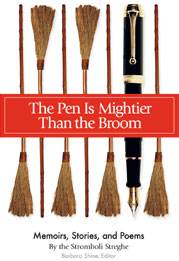

I worked with a marvelous group of women in the Washington, DC, metro area for nearly 12 years. We started as a handful of mostly unpublished writers (except for technical articles), and over time we began to see our personal essays in the Washington Post, Christian Science Monitor, Washingtonian and Common Boundary magazines, and literary journals such as The Sun and Potomac Review. Eventually we collected some of our best pieces in an anthology, The Pen Is Mightier Than the Broom: Memoirs, Stories, and Poems, which I describe as “52 short writings by 11 remarkable everyday women.”

From that group experience, I came away also with a pocketful of operating principles, refined through trial and error that I see as essential for a critique group's success. There are, of course, some nuts-and-bolts issues that call for a group consensus, such as when and where to meet and who leads the meetings. But those are not the most important concerns. The truly successful critique group — the one that helps every member toward her individual writing goals — is the one where all participants agree to the importance of commitment, safety and confidentiality, and focused critiquing.

“Your wholehearted commitment to the critique group will nourish your commitment to your writing self...”

Commitment: To the Group and the Writing Self

When we're serious about improving our skills and moving up in the writing community, we're just as serious about our critique groups. Members need to give those meetings a high priority.

So it's important that the group reach a consensus on the best meeting time and stick to it. Twice a month — for example, for two hours on the second and fourth Saturdays — has worked well for my groups; other groups meet once a month or once a week. The schedule you choose will be the product of [busy lives of members] X [seriousness of writing goals].

Sometimes one has to miss a session — Janice may have to fly cross-country on business, or Sarah has a sick child -- but usually one can schedule optional activities around the group meetings. I quickly learned to respond to requests for my time with, “Sure, I'll be glad to help next Saturday, but I won't be free until after 1:00.”

It can be hard to turn down social invitations that conflict with your group's meeting days, but other group members will appreciate your commitment and the reliability of meeting dates. Just practice this response until it flows easily: “Thanks for the invitation; I wish I could be there. But I have a standing appointment that I cannot miss.”

On the rare occasions when you absolutely must miss a meeting — say for a professional conference in Florence, or a doctor-certified case of pneumonia or childbirth — let the group leader know you'll be absent, and check in as soon as possible afterward by phone or e-mail. Show your interest in how the meeting went and ask for copies of work that was critiqued. Your comments for the other writers will doubtless be welcome, no matter when you offer them.

At the next meeting, be more THERE than you've ever been. Bring a new piece for critique, offer nuggets from your morning journal pages, or share news of an upcoming contest for writers.

Your wholehearted commitment to the critique group will nourish your commitment to your writing self: When you're excited about taking work to the group, you'll be excited about keeping a notebook for titles and characters, writing those practice pages every morning, and even about revising through second, third, or fourth drafts.

“Safety in the group also means that our writing will not provoke criticisms for the beliefs and behaviors we write about.”

Count on Safety and Confidentiality

Writers in a critique group need to feel total freedom in the work they bring to the group for review. My groups have always held that — as in Las Vegas — “what goes on here stays here.”

It's not just because we write about sensitive personal issues, which we do, but we may also be presenting material that could affect others if it were leaked. I need to know that I can share, through my writing, the details of critical episodes and not have those details broadcast further until I'm ready.

Each of us decides for herself when a story is ready for public reading, if ever. Sometimes one of us writes a story as catharsis, with no intention of publishing. Yet she can share that therapeutic writing with our group in trust that it will be held in confidence for her.

Safety in the group also means that our writing will not provoke criticisms for the beliefs and behaviors we write about. Groups can comprise a variety of races, religions, sexual orientations, educational achievements, and other personal histories, with roughly equal proportions of saints and sinners. If Dolores brings us a story about her “wild phase” as a new divorcee, our safety principle demands that we treat her words with the same respect we give a memoir by Mother Teresa. It's our job not to judge the outrageous behavior, but to help Dolores write that behavior in a way that makes its outrageousness irresistible to readers. We offer big chunks of tolerance; no judgments.

It's important, too, that each member of the critique group feels she's getting what she needs at the group meetings. Samantha may want the group to review her story's concept or structure; while Janice feels she needs help mostly with dialogue. Sarah and Terry appreciate help with their grammar and punctuation; but Dolores prefers that we keep our red pens away from her commas. Some writers will bring a finished story to the group, confident of its completeness and wanting only suggestions for where to submit it (sadly, this last type may not last long in a critique group, as they do not welcome criticism).

You need to tell the critique group what kind of help you want and ask for it explicitly. Also, don't be afraid to ask for extra support between meetings. Someone in your covey of generous women writers will certainly be willing to help you through a phone call, e-mail, or a one-on-one meeting. I've had meetings with individual members of my group on topics ranging from periods vs. semicolons to possible plagiarism to the scientific names for body parts.

The last safety issue is how critiques are handled: kid gloves or bare knuckles? Nobody goes to a critique meeting, holding her new baby snuggled close in its manila folder, only to watch that baby be sliced to shreds. Read on . . .

“Don't belabor spelling, grammar, punctuation...

try to use the group time for major elements of the writing.”

The Art of Gentle Critique

Sometimes I wish that “critique” started with a K, so I could say the golden rule is “Kritique with Kindness.” But that's an oversimplification, anyway.

Typically, a writer reads her story or essay aloud to the group, and the others give their feedback in turn. It's helpful to provide a copy for each group member to read along and make notes. The writer can then take the notes home with her immediately, or allow time for the others to re-read and send more detailed comments later.

But how can we make our criticism truly helpful? We don't need to coddle someone whose writing is floundering, but we shouldn't insult her, either. The gentle and, not incidentally, most useful critique includes compliments on what works well and suggestions to improve what's not working as well (if you cannot find anything that works well, at least compliment the writer for including an idea that could be developed into something that works well).

At the other end of the skill spectrum, don't be overwhelmed by a super-good piece of writing and find yourself unable to offer any suggestions. Everyone can improve.

Other basic rules of critique:

- Offer suggestions in terms of what “works” or “doesn't work” for you. Use your reader's eye to guide your comments.

- Be as specific as possible. Such phrases as “I like it” or “This is good” or “I don't get it” should not be part of the discussion.

- Offer suggestions, but don't do the rewriting. “Use a stronger verb here” is a better learning tool than “replace ‘walked slowly’ with ‘dawdled’.” You'll help your peer more (and sound less harsh) with “This is where the story REALLY starts” rather than “Move this paragraph to the beginning.”

- Don't belabor spelling, grammar, punctuation. We all need to get those things right, but try to use the group time for major elements of the writing. Detail cleanup can go into your written notes, or be handled in a later draft.

Focus on Skills

Try to stay focused on the writing that's put forth for discussion. It's tempting to dissect the story behind the story, begging for more details, the underlying rationale, the travelogue, the resolution of the problem, if any. But that is not why the critique group meets. Of course, we sympathize with a painful memory in a writer's personal essay, but the critique group should not try to provide group therapy. Rather, we are there to comment on how effectively the story is told and to help each other build writing skills.

We support the writer's healing and validate the importance of her story by helping her get power into the telling. If Sarah has written about victimization, and I ask, “How did you get into that situation?” she may talk for a good while, satisfying my curiosity but not advancing her writing (and not making good use of the group's time). It's better if I offer a suggestion: “Could you work in some background on what led up to that situation?” This she can take away and write into the story, if it's appropriate.

Instead of “What are you going to do next?” another critique group reader might tell Sarah, “I think your readers would appreciate an ending that mentions some of the options you're thinking about.” We wouldn't discuss those options in the meeting, but Sarah would go home with a valuable idea to strengthen the conclusion of her piece.

Don't be misled: This is not a problem only for writers of tragic, problem-based memoirs. Your group can just as easily be distracted by and lose valuable time to details of show dogs, grandchildren, elections, and the planning of English summer gardens.

The kinds of details a writer omits from her story may very well spark a conversation for another time, in another place. But that conversation is not part of a writing critique. Stay focused on the writing.

“Learn to accept critiques graciously.”

The Aforementioned Nuts and Bolts

Once you've established a meeting schedule, hold a meeting every time, even if only two or three of you can attend. One person should be in charge of sending reminders of the meeting date and time to everyone and taking RSVP's.

Here is a sample agenda that has worked well for my critique groups:

- Settle in and socialize — 10 minutes (latecomers have to socialize on their own time)

- Ask member for updates on their progress with submissions, contest news, upcoming or past conferences, recommended Web sites and publications, and such — 10 to 15 minutes

- Breathe (relaxation exercise) — 5 minutes

- Do timed writing practice from a prompt — 10 minutes for writing, 20 to 30 for sharing (without critique)

- Have four or five members read their work (up to about 1500 words per piece) and receive feedback — 60 minutes or more

- Confirm date and logistics for next meeting; adjourn.

A great deal of latitude is possible within this plan: Members can rotate the responsibility for facilitating the meeting and choosing the timed writing exercises. You could review longer pieces by fewer writers each time.

In another model, you might bring your story in copies to distribute to group members at this week's meeting, and get the feedback next time giving them a week or two to thoroughly review the work. This approach works well when they're writing books and need feedback on entire chapters.

One final note on the art of critique: Learn to accept critiques graciously. The writer whose work is getting comments is supposed to sit quietly, listening and making notes while her peers give feedback. No whining or defensiveness, and remember to thank everyone who offers comments. Each member who takes the trouble to acknowledge and review your work is an asset in your writing growth fund.

How To Be a Hit with Your Critique Group

- Take your best work to the group for review (not first drafts)

- Go over spelling, grammar, and format before you print.

- Don't ask the group to critique anything you have to serve up with an apology on the side.

- Prepare your manuscript in a legible standard font (12-point or larger), double-spaced, with at least 1” margins, on just one side of the paper.

- Number the pages and include your name, the date, and a title on the first page.

- Listen quietly while your work is critiqued, and thank everyone for their comments. Ask and answer questions, as needed, but stay focused on the writing.

- Offer thoughtful, respectful, and gentle attention to the work of other group members.

- Do your part in sustaining the group by sharing market news, resources for writers, and advice that has helped you. Take cookies to the meetings sometimes.

- Always, always let the group know how much you appreciate their help.

-------------

Barbara Shine is a freelance writer and editor who lives and works in Virginia's Northern Neck, an uncluttered, slow-paced region on the Chesapeake Bay. She writes creative nonfiction and articles and conducts workshops for others interested in writing the stories of their lives. Barbara's 2006 literary collection, The Pen Is Mightier Than the Broom: Memoirs, Stories, and Poems, earned second place for edited books in the Virginia Press Women's Annual Communications Contest; two of her essays in the book also won VPW awards.

The book is available in softcover and e-book formats at www.iUniverse.com, www.bn.com, www.amazon.com, and other online booksellers. Readers can purchase a copy signed by Barbara at www.bshinewrites.com.

Barbara Shine is featured in WOW! Women On Writing's March Issue,

Freelancers Corner: Finding Your Flock.